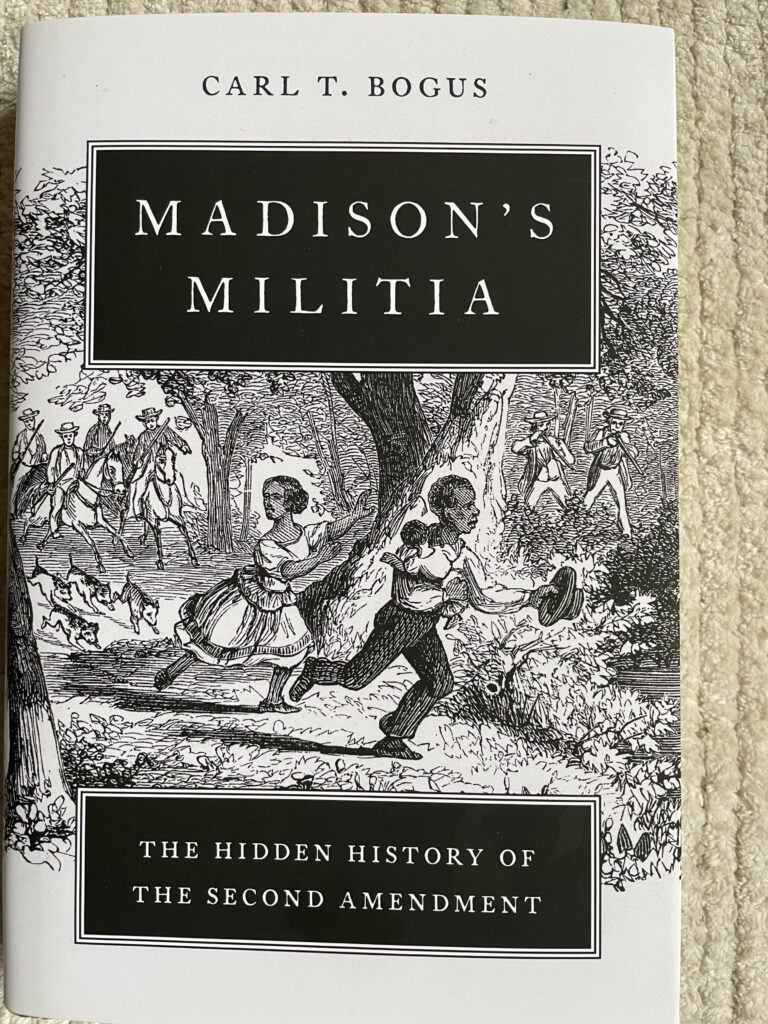

Madison’s Militia

By Carl Bogus

Published by Oxford University Press, 2023

Reviewed by David Lawsky

Text of the Second Amendment to the United States Constitution:

A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.

Introduction

Anyone attending the Presbyterian Church in Wiltown Bluff, South Carolina, on a Sunday in 1739 would have noticed the men carried guns and ammunition. South Carolina law required all men between 16 and 60 to be in the militia and to attend church every Sunday with their weapons. On September 9, services were interrupted by Lt. Gov. William Bull II, who had terrifying news: Blacks carrying banners and shouting “Liberty” had killed 40 White slave owners and their kin.

Some 100 members of the militia set off on horseback and found the Black rebels in a field about a dozen miles away. The militia attacked the 44 rebels, who fought back so fiercely they killed 21 White men before being overpowered. Surviving Black rebels were executed on the spot, their heads impaled on pikes. Others had fled as the battle began but were later captured and executed.

Slave uprisings were a continuing nightmare for Whites. Historians have identified 579 slave rebellions on land and sea, mostly between 1726 and 1800. The militia worked to protect White southerners from the possibility of Black rebellion, for example, by raiding plantations at night to uncover potential slave plots, but in 1788 slave owners faced a new danger.

State militia were under threat from the proposed new U.S. Constitution, its opponents said. Article 1, Section 8 snatched control of the militia from states and conferred it on Congress, opening the possibility the dominant northerners could eviscerate protection against slave rebellions.

Second Amendment politics

That threat gave birth to the Second Amendment, as Carl Bogus argued in a law review article. Now Bogus has written a full-length book, Madison’s Militia, adding rich historical context and details, showing how the Second Amendment arose from the politics of slavery in the eighteenth century.

Bogus examines the right to bear arms in England and four states, describes the desperation of slave rebellions and brutality of their repression, takes us to Revolutionary War battles where the militia fled in fear and depicts Patrick Henry’s fiery oration against the Constitution at the Virginia ratifying convention. He brings these elements together to argue that — whatever we may think now– the Second Amendment was vital to White southerners because it guaranteed state militia the unchallenged authority to rein in Black slaves.

Southern Whites may have fed the fiction to northerners that Blacks were content as slaves, but they knew better themselves. Georgia banned slavery in 1735 from fear of slave rebellions, eventually reversing itself under pressure from plantation owners who envied the wealth created by slaves in South Carolina. Thomas Jefferson, who owned hundreds of slaves, said the prospect of an influx of additional Black slaves into Virginia “filled [him] with terror.”

The militia calmed concerns by vigilantly policing plantations to preserve White power. What the militia were not, in either America or England, was an effective fighting force against professional soldiers. During the Revolutionary War, Henry Knox, later to be secretary of war in George Washington’s cabinet, called the militia a “receptacle for ragamuffins.”

Bogus describes these rag-tag soldiers in one battle after another, cutting and running when faced with English redcoats armed with fixed bayonets. This was not lost on James Madison, a proponent of a professional army, who argued at the Virginia constitutional ratifying convention that the United States “risked annihilation” if its defense were left to the militia.

Rusty muskets

President Washington, already skeptical of militia after his revolutionary wartime experience with them, called up 15,000 men to suppress the Whisky Rebellion in 1794 only to find that two-thirds lacked weapons. When York County, Virginia, did provide muskets, many were lost, sold, or allowed to rust within a few years.

Yet the militia were vital to the White South.

“The militia were ineffective as a fighting force but indispensable for slave control,” Bogus writes. This was underscored when a representative of South Carolina told Congress that its militia was unavailable to fight the British because they were needed at home “to prevent insurrections among the Negroes.”

Ratification debate

All of this became an issue in 1788 during fierce debate over the Constitution. Each state had called a special convention to vote on ratification and it seemed Virginia might be decisive.

In the Virginia debate, Madison, one of the principal authors of the Constitution, faced off against Henry, the former governor of Virginia known by generations of American school children for uttering the words “Give me liberty or give me death.” Henry sought weaknesses to attack the Constitution and looked to the powers of Congress enumerated in Article 1, Section 8, where the militia provided an excellent target.

At the Virginia ratifying convention Henry orated that the provision granting Congress authority “to provide for organizing, arming and disciplining the militia” would leave Virginia in a “deplorable” condition:

“[Congress’s] control over our last and best defense is unlimited. If they neglect or refuse to discipline or arm our militia, they will be useless; the states can do neither – this power being exclusively given to Congress.”

As was clear to everyone in the room, Congress could permit the militia to wither and leave Virginia prey to slave revolts. And whatever the reality might be, southerners believed a Congress dominated by anti-slave northerners might do just that.

The pro-Constitution forces mounted a strong campaign against the anti-federalists. Madison, Alexander Hamilton and John Jay portrayed the Constitution in the best possible light by writing a series of op eds in New York, later collected as The Federalist.

Bill of Rights

One sop to anti-federalists was to encourage them to draw up a series of amendments and chief among these was a bill of rights, opposed by Madison as unnecessary. He later had reason to change his mind.

Madison ran for Congress in a district gerrymandered under the influence of Henry, a political enemy, who stuck him with a majority of anti-federalist voters. To win support during the campaign, Madison told voters he had altered his views and would write and propose a bill of rights if elected to Congress. He was, and he did.

During a speech to Congress on June 9, 1789, Madison proposed his bill of rights, including what he called the “great rights” of trial by jury, freedom of the press and liberty of conscience. The text of the speech covers other matters, too, but has nothing to say about the right to bear arms.

Nonetheless, the Second Amendment was part of his package. The version proposed by Madison was almost identical to that adopted, except that it included a right to refuse military service by reason of conscience for groups like the Quakers.

Individual gun rights?

Bogus asks whether Madison’s version and the wording eventually adopted were meant to provide an individual right to arms separate and apart from the militia. For that to be true, Bogus argues, the amendment would have had to contain three separate propositions:

- A well-armed and well-regulated militia is the best security of a free country.

- The right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed.

- No person religiously scrupulous of bearing arms shall be compelled to render military service in person.

Madison instead placed all three in a single sentence because “he was writing a single provision with three interrelated parts,” Bogus tells us. Congress dropped the clause on conscience but kept the other two, making their close relationship even clearer.

Still, Madison’s original version teaches us something about the two clauses which remain. The provision for conscientious objection makes no sense unless the amendment is about the militia. The right to bear arms responds to the concerns of Patrick Henry because it bars Congress from disarming the militia, whose members – as we have said — usually provided their own weapons.

Madison was not the first in America, nor in the wider English speaking world, to talk about a right to bear arms. The constitutions of Pennsylvania, North Carolina, Vermont, Massachusetts and the English Declaration of Rights in 1689 all mentioned it, but in contexts that had purposes and meanings different from the Second Amendment.

Bogus goes into great detail about each of the four states and also makes this general argument: the arms provisions were written near the start of the Revolutionary War when states held romanticized notions of the militia, following their success at the battles of Lexington and Concord. They believed men needed to bear arms for the militia so they could fight for their country.

Only later did it become apparent the militia were unable to operate as disciplined fighting units and a trained, professional army was needed to win the Revolutionary War. The right in those four states was nothing like England, which had a different approach for its own reasons.

English gun rights

Bogus spends an entire chapter giving us the background behind the English Declaration of Rights, which he explains was not for individuals but rather to enhance the authority of Parliament at the expense of the king. The Declaration empowered Parliament by saying Protestants (but not Catholics) could have arms “as allowed by law.” The law Parliament chose to pass had a means test that excluded gun ownership by 98 percent of the population.

By contrast, the Second Amendment was designed to ensure armed militia were able to preserve the security of White people against slave rebellions, a task to which they were more than equal — even if unfit for defending the country.

At the beginning Bogus makes clear that although he is a law professor this is a book about history, not law. Bogus is disciplined enough that he neither discusses today’s controversies nor reflects on development of the law, but readers who accept his carefully developed historical thesis may find themselves asking, “How did our culture and jurisprudence stray so far from the original meaning of the Second Amendment? How did the Supreme Court wind up finding an individual right to guns in its Heller decision in 2008 and Bruen decision in 2022?”

Thirteen words

The answer is that the Supreme Court decisions toss out half the amendment, dismissing the first 13 words variously as “prefatory” or a “preamble.” By relying on the last 14 words of the Second Amendment as the only “operative” clause the court has radically altered its original meaning.

A court that relies on history to guide its rulings better get it right, because if the history is wrong the decision probably is too. The story Bogus tells describes a Second Amendment in which every one of the 27 words counts and is — to use the Court’s word – operative. That is at variance with the Court version of history and demands serious consideration, requiring a reasoned reply by those who would disagree.

In the last two sentences of his book, Bogus allows himself to wonder what the reaction of Madison and others would be to today’s gun culture and the claim that the Amendment is about an individual right to arms. His conclusion:

“They would have been astounded.”

ENDS